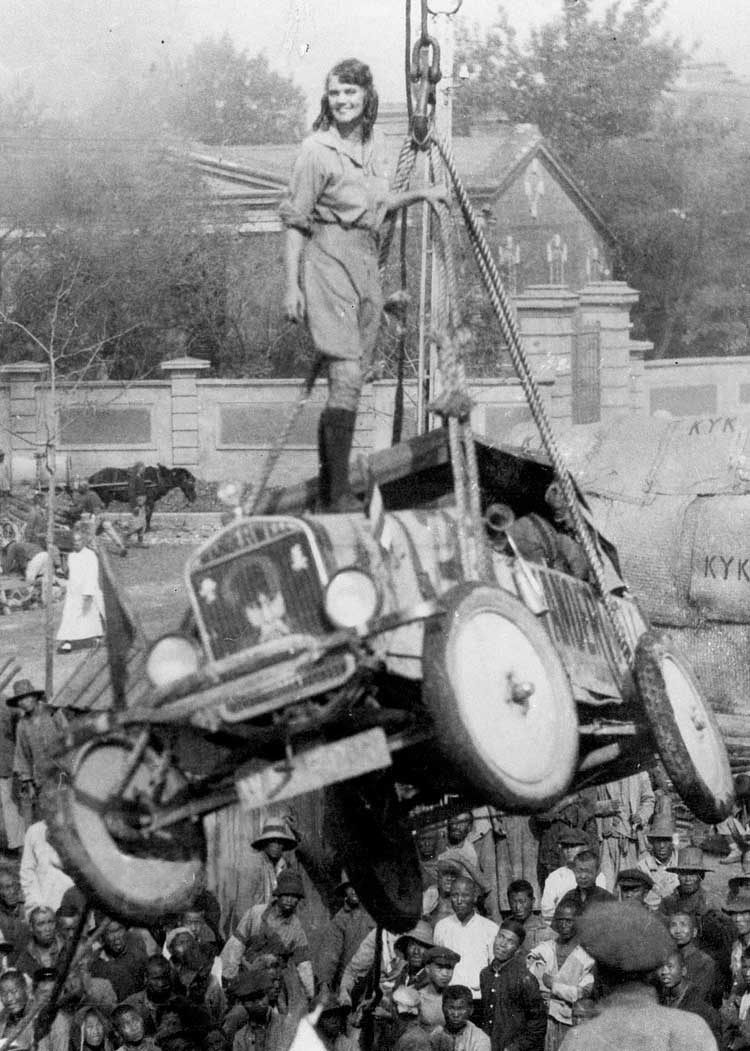

I recently came across this photo of Aloha Wanderwell, an explorer, vaudevillian, a female Indiana Jones. She is largely forgotten in today’s history books, even though her list of achievements is impressive in any century. Not only was she the first woman to drive around the globe, she also was involved in a murder mystery.

Achievements:

- First woman to drive around the globe. (Wikipedia)

- Drove 43 countries in a Ford Model-T at age 16.

- Earliest films of the Bororo people of Brazil.

- Traveled 380,000 miles to 80 countries in the 1920s.

- First across India and Cape Town to the Nile.

- First woman to fly Brazil’s Mato Grosso.

- Filmed the first flight around the world.

- Member of the French Foreign Legion.

- Films at The Smithsonian & The Library of Congress.

- Women’s International Association of Aviators.

- Started Work Around the World Educational Club.

Here are excerpts from her obituary, taken from the NYTimes series “Overlooked,” written by Carrie Rickey:

The ad in The Paris Herald called for “a good-looking, brainy young woman” willing to “forswear skirts” and “rough it” in Asia and Africa for an unspecified expedition.

“Be prepared,” it said, “to learn to work before and behind a movie camera.” It was 1922.

Idris Welsh, a 16-year-old student at a convent school in France who was crazy about movies, read the ad and was hooked.

She applied and was given the job of mechanic in an ill-defined endeavor that involved filming a team’s travels as it motored around in 1917 Model Ts. At 6 feet tall, blond and attractive, Idris quickly became the face of the expedition, which captured her adventures in a series of movie travelogues.

She clocked 380,000 miles in the 1920s, traversing six continents, often in places where paved roads were unknown. Newspapers called her “the Amelia Earhart of the open road.”

She radiated star quality onscreen and electrified lecture audiences with her tales of the road.

The leader of the expedition was Walter Wanderwell (born Valerian Johannes Pieczynski in Poland), a suave promoter with a checkered past that included a prison stint as a suspected German spy in the United States during World War I. He called himself the Captain.

In preparation for the first trip, Idris took on her childhood nickname, Aloha, and tacked it onto the Captain’s surname. Aloha Wanderwell became her nom de route.

On the team’s first trek, from 1922 to 1925, Wanderwell drove in the expedition’s parade of Fords from Nice, France, across Europe and then through Asia, from Mumbai to Kolkata on India’s broad shoulders, and then up to China. After entering the U.S.S.R. and making her way to Vladivostok in 1924, the Soviet Army named her an honorary colonel for “being the first demoiselle to pilot a motorcar to Siberia.”

By the time of her next expedition, from Cape Town to Cairo in 1926, she had married the Captain. This time she helped him improvise. They used kerosene for gasoline, crushed bananas to grease the gears, and water and elephant fat for engine oil.

Idris Welsh was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, on Oct. 13, 1906, and grew up in British Columbia. To strains of ukulele music on the gramophone, the towheaded Idris often entertained her family by dancing the hula, happy as the center of attention. Novels by Joseph Conrad stoked her craving for adventure, and Screenland magazine fanned dreams of stardom.

“Mary Pickford was her idol — she was movie-crazy all her life,” said Christian Fink-Jensen, who with Randolph Eustace-Walden wrote the biography “Aloha Wanderwell: The Border-Smashing, Record-Setting Life of The World’s Youngest Explorer” (2016).

By 12, Idris had traveled unaccompanied by rail and oceanliner from her boarding school in Canada to England, to be with her mother. At 15, she began taking driving lessons from a dashing war hero.

In her unpublished memoir, “The Driving Passion,” she recalled her time in his cherry-red Peugeot, observing “how the confines of a car, its reassuring purr and motion, breeds an extraordinary sense of isolation, intimacy.”

Itching for further adventure, she spotted the ad in The Paris Herald.

With her mother’s permission, Idris joined the Wanderwell crew. Like everyone else in the unit, she dressed in a military jacket, jodhpurs and riding boots.

Famously, in 1931, Wanderwell and the Captain traveled to Bahia, Brazil, to search for the explorer Percy Fawcett, who had vanished while looking for the supposed Lost City of Z. (They left their son and daughter in the care of Wanderwell’s mother, in foster homes, and later with her half sister, Miki.)

The Captain, a lifelong philanderer and suspected rumrunner during Prohibition, lived on a schooner, named Carma, 28 miles south in Long Beach. He hoped to repair it and sail it to Tahiti.

On the night of Dec. 5, 1932, the Captain was on the schooner with his sleeping children when a stranger wearing a long gray coat boarded and asked to see him. A group of would-be passengers who were waiting for the boat to sail directed the man to the room where the Captain consulted maps. Soon after, the passengers heard shots. Some ran onto the fogbound deck, looking for the stranger. Others found Wanderwell slumped against a banquette, fatally shot with a single bullet in his back.

“Globe-Girdling Husband of Winnipeg Woman Found Dead” read a headline in The Winnipeg Free Press the next morning.

William Guy, a disgruntled employee who had worked for the Wanderwells in South America, was charged with the murder but acquitted. The crime remains unsolved.

“The list of possible killers with a motive would have made Agatha Christie’s head spin,” Eustace-Walden said. “It could have included husbands, boyfriends, jilted women, jilted business partners, an agent of a foreign power, rogue police, and Aloha herself.”

As her husband might have done, Wanderwell used the publicity surrounding the Captain’s death to promote their film, “River of Death.”

In 1933 she married a gas station attendant named Walter Baker and traveled to India and Australia with him, making movies for much of the 1930s.

They celebrated their 60th anniversary two years before his death, in 1995. She died the next year, at 89.

In 1980, when she was 74, Wanderwell gave her last known lecture and screening, at the Museum of Natural History in Los Angeles.

She asked audience members how they traveled. By car and plane, they answered.

And then she dazzled them with movie clips of her travels by car before superhighways existed, and by plane when commercial airlines were in their infancy.

Read more about Aloha here: