It all began when I was sitting on my parent’s porch in Utah one summer night as a young girl, listening to the rumbling of the Southern Pacific train in the distance, smelling the freshly mowed grass, and reading On the Road by Jack Kerouac. I read about the mythical figures of Sal and Dean Moriarty, thinly disguised characters representing Kerouac and Neal Cassady, and felt myself caught hook, line, and sinker by the jazz-like prose reflecting back a central theme of the book and my own thinking:

I have never been interested in “companionship,” or quiet love. Give me wild passionate sensual love, the kind of love that makes you feel like you are floating, swooning, and being thrown off a cliff… or give me nothing.

It’s not about the destination, it’s about the journey.

Like sitting in a rowboat in a blackened sea, and watching the sea light up with phosphorescence, the words seemed to illuminate a life philosophy I didn’t even know I had, appearing letter by letter before my eyes:

My whole wretched life swam before my weary eyes, and I realized no matter what you do it’s bound to be a waste of time in the end so you might as well go mad.

As a teenager, I loved reading literature, but I never connected to the protagonists: I always connected to the misfits and outcasts. For example, I loved reading the Bronte sisters, but I never related to Jane Eyre — I related to the madwoman in the attic. I was completely uninterested in Cathy and Edgar Linton of Wuthering Heights, laying on the settee in a posh house — I was wild for Heathcliff. I wanted to gallop across the moors in the pouring rain, the in-between place, neither Thrushcross Grange or Wuthering Heights, and not to ramble, but to race in such a wild way that mud splashed into my hair and I became my own lightning bolt, striking the wild grasslands with my light.

Woo! I got carried away with that vision. (I could be caught up in Kerouac’s style or maybe I just drank too many cappuccinos this morning.)

The point is, I never related to the regular humans; I related to ones that normal people locked out of sight, the ones who disrupted ordinary life, the wild passionate ones. Writer Jean Rhys must have felt similar to me as she wrote an entire novel about that madwoman in Rochester’s attic, a story about how that woman went mad in the first place. It’s called Wide Sargasso Sea, and I don’t remember it all except that it involves sensual dancing, lush nature, flaming birds, and a woman who refuses to follow the social norms.

Kerouac understood, I think.

I wrote these words from On the Road on a scrap of paper and taped it to the little mirror in my bedroom:

The only people that interest me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones that never yawn or say a commonplace thing but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue center light pop and everybody goes ‘Awww!’

Which might explain my eclectic group of eccentric friends and why I was drawn into the theater and circus life, the type of life who attracts people who choose a life of freedom over a life of fancy cars and big houses.

After reading On the Road, I decided I, too, would become a beatnik poet. It was 1987 when I wrote this poem on my parent’s old typewriter:

If you want to be a star, you’ve got to live in the sky.

Fly child. You’re only young once. You only come this way once. Be a saint when you’re eighty-five.

Run like there is no tomorrow. Live fervently, with a raging passion.

Every instance hurled your way has made you what you are this moment.

Suck it. Nurture it. Set the world on fire.

Never wait. Never quit. Don’t slow down when it gets rough.

Race it, push it, don’t try to tame it. Open your mouth and let it rush through you. Deaht is not an option. Sailing on a cloud is.

Never be hushed. You and your Mother Earth are one.

She takes care of her own.

What it is, is you. You’re running too fast to get stepped on.

Adventure, laughter, passion… that’s what life is about.

Live it.

I dreamed of tying all my belongings into a kerchief, tying them to a stick, and hopping onto the Southern Pacific Railroad in the middle of the night, not caring where it was going, as long as it took me somewhere new.

Just like Kerouac:

I was surprised, as always, by how easy the act of leaving was, and how good it felt. The world was suddenly rich with possibility.

You can imagine how popular my budding philosophy was in my Mormon culture. Lucky for me, my parents found me more entertaining than dangerous. The only reference they had to beatniks was a story they told when they went to visit my cousin in San Francisco. My Dad would laugh and say, “We had to sit on cushions on the floor.” My Mom would wrinkle her nose and say, “Ugh, the whole place smelled like incense. I think they were beatniks.” She said the word “beatnik” like she had just accidentally bit into a lemon. Tart, bitter, unappetizing, but in the end, good for the soul.

While my parents didn’t encourage my beatnik phase, they loved my poetry and encouraged my writing. (As #5 out of 6 kids, my older siblings had set the bar pretty low and as long as I stayed out of jail and was home by midnight, my parents were happy.)

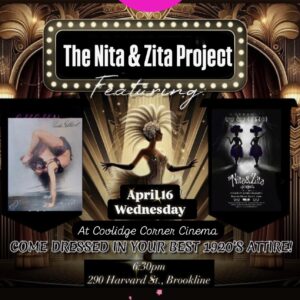

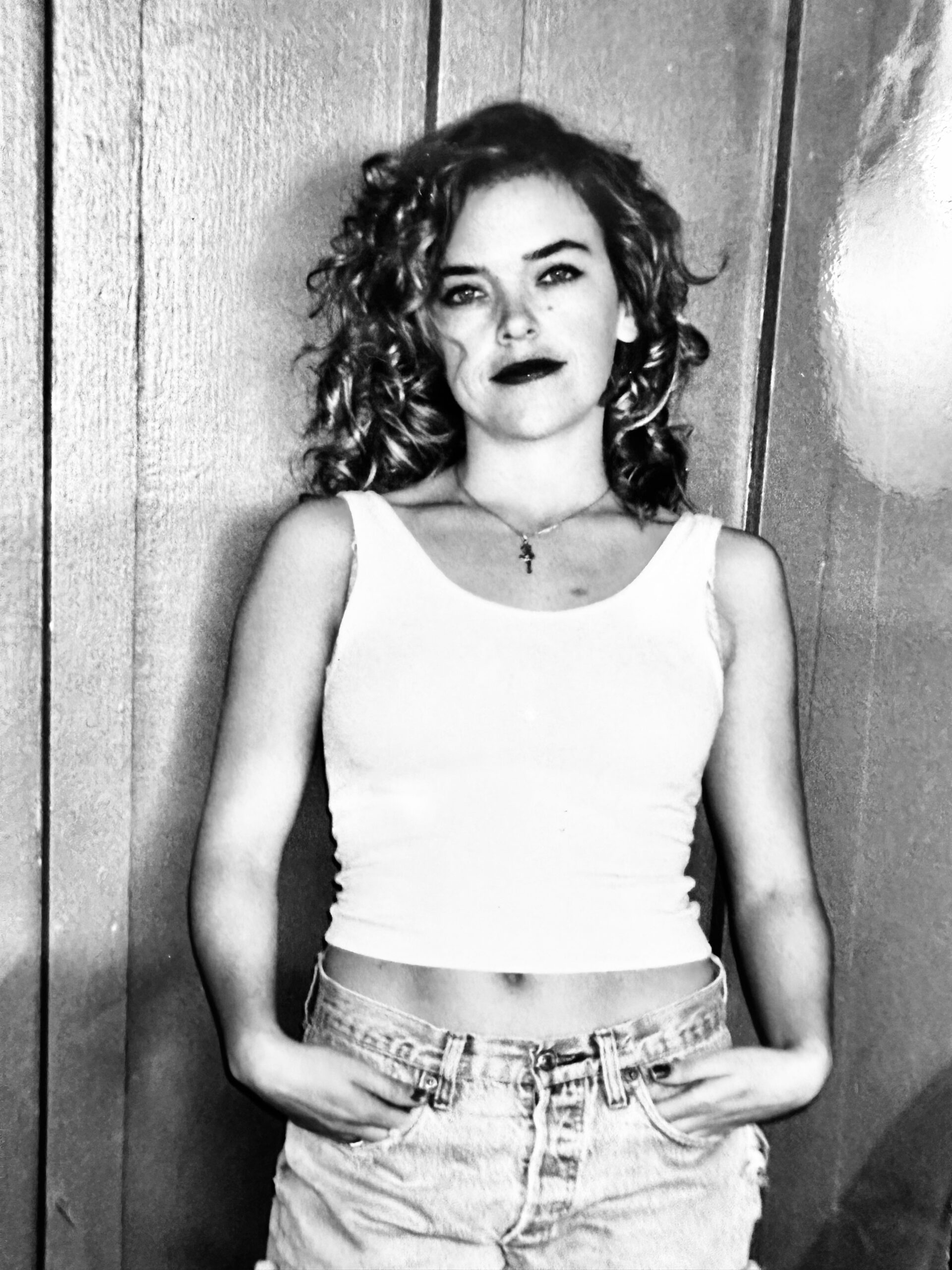

The first night I connected with Kim was a beatnik-type of night. I read her my poetry and went to listen to the Chuck E. Weiss sing the blues at my local coffee shop, where we met Tom Waits. We stayed up late into the night, and I played more Tom Waits for her, Leonard Cohen, Eartha Kitt, and read her poetry: Whitman’s Song of Myself, Yeats poems on fairies and wine, and of course my highlighted paragraphs in the Diaries of Anais Nin. We stayed together every day after that, and anyone who knew me knew Kim too. Much to my parent’s chagrin, Kim and I loved sitting on the floor watching the incense smoke curl into the air, like a genie coming out of a bottle so we could make wishes. We read poetry to each other and wrote poetry together. Sometimes at night in my single apartment in Hollywood, I recited poetry while she danced in my short white nightgown with a wreath of flowers in her hair. I read “Everyman” by Tennessee Williams, and during the last section, Kim would be in an arabesque until I’d say: “And then her body broke, in two parts like a stone…” Then she would collapse onto the floor. Then we’d collapse on my bed laughing and come up with more performance art pieces, just for us.

Eventually, On the Road became another book on my “Shelf of Books that Changed my Life,” joining the ranks of Brothers Karamazov by Dostoyevsky, Ulysses by James Joyce, Walden by Thoreau, and the Diaries of Anais Nin.

It’s been a long time since I wrote that poem in 1987. I was 18. Now I’m 53. Like the bird in Wide Sargasso Sea, my marriage ended in a burst of flames.

Kerouac wrote:

My aunt once said that the world would never find peace until men fell at their women’s feet and asked for forgiveness.

I like the idea of men falling at my feet asking for forgiveness, but I’m not sure it would help… there’s been too much loss. My father is gone now, my Mom has slipped into dementia. Kim chose to leave the planet back in 2018, dancing into the air like flaming golden incense smoke curling and dancing into the sky, before disappearing from sight.

A pain stabbed my heart, as it did every time I saw a girl I loved who was going the opposite direction in this too-big world.

I recently bought ten copies of On the Road to give as gifts to all the graduating seniors I knew. I gave it to them with a note: This book changed my life. I hope it changes yours too.

I meant change it for the better of course. I once nearly came to fisticuffs with a handsome dark-haired-blue-eyed boy who proclaimed that Kerouac had ruined his life, that the book should be banned because it had made him irresponsible, inspiring him to hit the open road and travel.

You are missing the point, blue-eyed boy.

Loving freedom doesn’t mean being irresponsible. I’m absolutely mad for freedom and I’m also very responsible.

Kerouac wrote: I believed in a good home, in sane and sound living, in good food, good times, work, faith and hope. I have always believed in these things. It was with some amazement that I realized I was one of the few people in the world who really believed in these things without going around making a dull middle class philosophy out of it. I was suddenly left with nothing in my hands but a handful of crazy stars.

A handful of crazy stars sums up exactly what I’m left with after all the loss.

When I came across the poem I had written, I wondered, if I met my 18-year-old self today, would I tell her to stop trying to catch those crazy stars? Would I tell her to calm down, choose the safe path, to maybe not love so much because, young Marci, with all that love there is so much pain coming down the tracks and it will hit you like a runaway freight train, bring you to your knees, make you question your very existence.

Not only would I not discourage young Marci, I would actually hand her On the Road and tell her that I wished her endless nights of burning burning burning like a roman candle, exploding into a summer night. That eruption of sparks lighting up the darkness is caused by one thing only: love. I would tell her that in the end, after it all burns away, only the love remains.

Kerouac wrote:

“As we crossed the Colorado-Utah border I saw God in the sky in the form of huge gold sunburning clouds above the desert that seemed to point a finger at me and say, ‘Pass here and go on, you’re on the road to heaven.’”

I don’t know what his idea of heaven was, but for me, it’s putting my belongings into a small bag and boarding a train on a warm summer night in Venice with my teenagers; it’s writing stories about Kim and my backpacking adventures and having thousands of young women write me to ask how I dared to go on so many adventures (cue book recommendation); it’s suddenly stopping the car on the way home from school in October when I spot a maple tree so beautiful, I’m compelled to stomp and crunch with the kids, hoping that for the rest of their lives, whenever they smell that Autumn smell of apple trees and maple syrup, dancing wind awakening the darkness, they will forever have the memory of their wild madwoman mother who made them get out and throw the leaves in the air like confetti, insisting they must never miss a chance to create their own light, to dance, leap, and roll in the golden leaves. As Robert Frost said, “Nothing gold can stay.”

Cherish it.